To a certain extent, Dear Reader, today’s pontification will apply to novelists and short fiction writers as well as to those of us who specialize in non-fiction. But mostly, I’m talking to non-fic writers.

To a certain extent, Dear Reader, today’s pontification will apply to novelists and short fiction writers as well as to those of us who specialize in non-fiction. But mostly, I’m talking to non-fic writers.

It has been said, “You do not need to know everything about a subject to be considered an expert on that subject, you just need to know where to go to get the answers.” This saying was posted above my desk when I worked for a publishing company that put out three daily newspapers, a dozen or so monthly magazines and a few books each year. I was Production Manager, but I also did a fair amount of writing for some of our publications.

I found a good deal of truth in the saying… and a fair bit of danger.

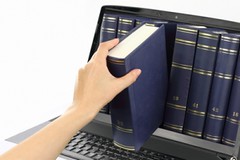

The dangerous side of this thought has increased considerably with the advent of the Internet. It used to be that research materials were comprised mostly of printed books, periodicals and papers by scholarly types. Most of it could be trusted as accurate and professional. Unless the books were printed by a vanity press, someone had done some fact checking during the vetting process of publication.

Where We Research

But today most people don’t turn to encyclopedias (many young people don’t seem to know what an encyclopedia is) or a periodical index, they key a search term into a Google bar and look through the top results listings for the information they seek. In itself, this is not a bad thing. I do it too. For the most part it is, in fact, a wonderful thing to have so much information at your fingertips at a moment’s notice without even having to change out of your pajamas. But it can be risky as well.

The Internet does not have fact-checkers. Even known resources like Wikipedia are comprised of user-submitted articles that probably have not been checked for accuracy. Someone who writes authoritatively can feed the public a complete line of bull, and few will know it. It is important, therefore, to do your own fact checking. I recommend a minimum of three independent sources to count a fact as verified. The key word here is *independent*. If the three articles are worded very similarly it is probable that they all came from the same author, in which case they are not actually validating one another, only corroborating what he or she is presenting as truth.

Using Our Knowledge

Naturally, if you are writing on a subject about which you have a great deal of innate knowledge, your fact checking can be minimized. You can write from your own experience, needing to check only critical details. If, for example, I write an article on the correct way to cut a bridle joint for a piece of furniture, I can describe the way I routinely cut a bridle joint – other furniture makers may prefer a different way. I favor hand cutting with chisel and back-saw, another may prefer the table saw method, yet another may prefer a router table. All work, which is best depends on your tools and skill-set. To be complete, I could describe them all, but would want to do a little research on the methods I don’t use myself to be sure I got the tool set-up right. Where you are submitting your article will also have an effect on how much fact-checking you should do.

Why We Research

If submitting to a trade magazine, they will have a fact checker who will go over your article before publishing. A glaring error will insure rejection. If everything else is good, they may ask you to correct the error and resubmit. If they do, you can bet you’ve been flagged as someone who is less than reliable and will be watched if you submit other articles.

Much the same for professional eZines. Many print magazines have an on-line version, and these often have expanded content that is much easier to get into than the print version. Prove yourself here and your move into the lucrative print edition will be easier.

Content mills rarely check facts; just your quality of writing. If the client is not an expert in the topic on which you are writing, you may get away with being sloppy because your name will not appear on the article. If the client is an expert, just doesn’t have time (or ability) to write his own content, or if his readers point out errors in his articles you can be sure it will hurt your standing with the editors. The only way to make money with a mill is to write a lot of really good articles and work your way up the list to where you get the better paying work as a favored writer. Factually sloppy work will not get you there.

If the work is to be published on your own blog or in a book under your name errors in your work, if spotted, will come back directly to you. You will also be fielding the questions. So, if you decide that a niche blog on refurbishing fire hydrants would be lucrative, you read a few books or do research on-line to get the basics, then start writing, make sure you’ve bookmarked your sources. If you get a question like, “On page 147 of your book you state that the knee-knocker bolt threads into the whatzidigger for ¾ of an inch. Can you tell me what the thread depth and pitch are on that bolt?” and you don’t actually know anything about fire hydrants, you’d better know where to go to get the answer.

Summary

Non-fiction writers can write good articles about subjects on which they are not acknowledged experts, but they must be careful in validating the facts they use in the articles or books to be sure the information they are passing along is accurate. Use only trusted resources or cross-check facts through multiple independent sources.

Welcome to the Golden Age of Fact Checking by Greg Beato | September 20, 2012

Allan, the “line of bull” is so appropriate! I use Wikipedia extensively – for fiction. As long as my story has the ring of truth, my research succeeds.

Reminds me of the Dictionary game, commercially sold as Balderdash. May the best liar win!

I’m off to find the richest deposits of Unobtainium for my next story…

Cheers,

Mitch

I’ve read a few articles here and there, mostly on blogs, where I could tell “creeping error” had played a part. Someone read something somewhere, decided to add it to their content, tweaked it a bit to avoid copyright claims and changed the meaning just a little in doing so. Each time this happens it gets a little more off target. Sort of like that parlor game where someone whispers a two or three paragraph story to the first person sitting in a circle, that person whispers the same story to the next person, trying to be as accurate as possible. Then the last person tells the story out loud and this is compared to the original story. It’s often amazing how fouled up things get!